It’s really useful to understand the structure of noun phrases. Along with verb phrases, they form the backbone of all our written and spoken language. They can be short and concise (a single word – yes, even a single word can count as a ‘phrase’ because there is always the opportunity to add extra detail …) or they can carry huge amounts of information.

Looking at the brief film descriptions you see in television listings is a great starting point for learning about noun phrases.

Simple Noun Phrases

So, we’re going to start with a single word. We call this the head of the noun phrase.

Simple noun phrases consist of a single noun (or pronoun), or a determiner + noun. Each of the genre nouns above is the head of a simple noun phrase. From the denotations and connotations of each word, we can get a good idea of what a film will contain.

horror

a film designed to horrify, usually through the depiction of the supernatural and violence [DENOTATION]

dark tone; monstrous happenings; associated feelings such as fear, shock, loathing, dread [CONNOTATIONS]

biopic

a film based on the biography of a well-known public or historical figure [DENOTATION]

true, but dramatised with some fabrication or manipulation [CONNOTATIONS]

Complex noun phrases: pre-modification

While a single head noun will give a broad sense of a film’s type, TV listings will often use words in front of the head to give readers a more precise understanding of a particular film. We call these complex noun phrases because they contain modifiers.

Pre-modifiers come before the head noun in a noun phrase. They can be adjective phrases, nouns or non-finite verbs (usually -ing present participles and -ed past participles).

The examples above are defining modifiers – they limit the range of reference of the head noun by specifying something distinctive about the film genre. For example, a comic film could be defined as

a slapstick sports comedy

a battle-of-the-sexes comedy

a fashion-industry satirical comedy

a culture-clash comedy

A Western could be defined as

an epic western

a Spaghetti western

a spoof western

a Civil War western

Each of the modifiers provides additional information refining our expectations: the adjective ‘spoof’ suggests a film that will mimic the features of a traditional western for comic effect; the noun ‘Spaghetti’ suggests a western in the style of the Italian director Sergio Leone. The words tend to be objective, reflecting qualities that are easily observable or quantifiable.

Modifiers can also be added to communicate a reviewer’s opinions. We call these evaluative modifiers – the examples below have positive connotations.

These modifiers come before the defining modifiers and are subjective – they reflect a particular person’s point of view.

a technically-brilliant, occasionally harrowing war drama

a thought-provoking period drama

a beautifully-rendered animated adventure

a spectacular fantasy adventure

Evaluative modifiers may comment on the physical features of filming (technically-brilliant, beautifully rendered), or may reflect the reviewer’s emotional response (thought-provoking, spectacular).

Evaluative modifiers may comment on the physical features of filming (technically-brilliant, beautifully rendered), or may reflect the reviewer’s emotional response (thought-provoking, spectacular).

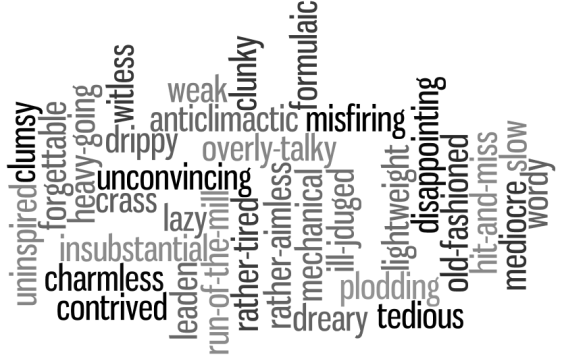

Evaluative modifiers can also communicate negative opinions.

an uninspired teen romance

a plodding spy thriller

a rather simplistic action adventure

a heavy-going biographical drama

From these examples, you can see how to build up strings of words before the head noun in a noun phrase to shape the meaning. Non-finite verbs like uninspired, intriguing, plodding, affecting and heavy-going, and adjectives like enjoyable, dreary, stylish, watchable and crass control our response to the head word. We can use degree adverbs like very, rather, quite, incredibly to refine the modifiers.

Compound modifiers are common because they communicate a lot of information in a small space. For example, effects-heavy, stop-motion, Flintstones-esque, part-animated. Coordinating conjunctions are also often used to link strings of modifiers, or to create contrasts. For example, crass, gross and witless; frantic but fun.

Complex noun phrases: post-modification

Noun phrases can also be post-modified by adding information after the head noun. The most common linguistic structures are prepositional phrases (starting with a preposition), relative clauses (starting with the relative pronouns who, which, that, where i.e. ‘in which’), and non-finite clauses (starting with non-finite verbs: usually -ed past participles or -ing present participles).

a charmless sports comedy based on a true story

(non-finite -ed clause)

a spectacular adventure brimming with breezy black humor

(non-finite -ing clause)

Low-budget action movie about a daring escape from a PoW camp

(prepositional phrase)

a compelling thriller that paints a devastating picture of the global finance industry

(that relative clause)

a nail-biting creepy classic horror which is a spine-tingling delight

As you can see from these examples, the post-modifiers can also include defining modifiers (true, global finance) and evaluative modifiers (breezy, devastating, spine-tingling). This is because there are also noun phrases embedded in the post-modifying structures:

- post-modifying prepositional phrases are made up of a preposition + noun phrase

special-effects-laden sci-fi comedy about a teenager who travels back in time

film-noir horror with a mean and moody landscape

quirky animation for the discerning

uplifting fantasy from the makers of the award-winning cartoon

- post-modifying non-finite clauses are made up of a non-finite verb (+ preposition) + noun phrase

tremendously exciting action thriller showcasing amazing martial arts skills

decent romance featuring A-lister Hollywood stars

period drama telling a tale of doomed love in 19th-century New York

brash musical adapted from the hit Broadway show

- post-modifying relative clauses are made up of a relative pronoun + verb + noun phrase/adjective phrase

classic western which exploits the tragic resettlement of the Cheyenne by the US government

whimsical comedy that becomes increasingly thought-provoking

OR

relative pronoun + noun phrase + verb

comedy where the new girl struggles to find her way in an American high school

dreary adventure in which an assassin is hired to hunt down a girl in witness protection

A noun phrase can carry a huge amount of information – by carefully selecting the type and tone of the pre- and post-modification, TV listings can help us to choose whether we will enjoy a particular film .

Are you going to watch?

Use the examples below to test your knowledge. Find the head noun; work out what kinds of modification have been used; and finally, think about the semantic effects created. Which films would you want to see?

Well-played but predictable comedy in which an uptight 30-something reconnects with her hippy mom

Commendable mystery

Tedious zombie-slaying adventure

Stylish and gritty drama based on a true story

Misfiring fantasy featuring four interconnected stories

Warm-hearted animation for the whole family