To start, an anecdote … (thank you Leah) ….

Approaching each speed sign, a driving instructor’s mantra was “It’s a limit, not a target.’ One sign – two meanings. Does the number in the red circle tell us what to aim for? Or, does it define a boundary? A driver who always drives at the speed indicated on the sign, hitting the target like an elite bowman, interprets the sign as a goal; the driver limiting speed to below the 30mph in urban areas or the 70mph on motorways is perhaps recognising the boundaries set to ensure the safety of pedestrians or other road-users.

This example is not really ambiguous since we all understand the function of a speed sign, but the principle holds for poetry. One word – two fields of reference. Two fields of reference – semantic ambiguity that engages the reader in a dramatic tension.

A poem like the short lyric ‘Spellbound’ written by Emily Brontë (1818-1848) provides a perfect example …

The night is darkening round me,

The wild winds coldly blow;

But a tyrant spell has bound me,

And I cannot, cannot go.

The giant trees are bending

Their bare boughs weighed with snow;

The storm is fast descending,

And yet I cannot go.

Clouds beyond clouds above me,

Wastes beyond wastes below;

But nothing drear can move me:

I will not, cannot go.

So how do we begin our analysis?

Having read through the poem from beginning to end, try to answer the questions below. After each question, a sample paragraph will explore some of the ideas you may have considered. The important thing to remember is that the interpretation offered here is just one possible reading. If you come to different conclusions, try writing your own sequence of paragraphs in order to explore your personal response to the poem.

1. Introduction

What is the main focus of the content?

The content of ‘Spellbound’ focuses on a storm, and the repetition of the first person pronoun”I” suggests that the poem offers a subjective account of a personal experience. We see the scene as the narrator sees it – the poem is a very private expression of one individual’s response. The writing is powerful and intense, reflecting both the external physical landscape and the internal emotional state of the narrator.

2. Key ideas: nouns and modifiers

What do the nouns and modifiers tell us about the content?

Brontë gives the landscape a physical presence with the concrete nouns linked to the natural world (“trees”, “boughs”) and the weather (“winds”, “snow”, “storm”, “clouds”). The atmosphere, however, is created through adjectives like “wild”, “bare” and “drear”, and the adverb “coldly”. These words tell us something about the literal scene, but also reflect the narrator’s mood. The use of pathetic fallacy helps us to understand that the poem is about more than just a description of a place at a certain moment in time.

3. Key ideas: themes

How does the poet use the words, the rhyme scheme and the form to develop her central themes?

The theme of vulnerability is developed in the perspective of the poem. The attributive adjective “giant” and the contrasting prepositions “above/below” make the narrator seem insignificant in the landscape. This is reinforced by the parallel noun phrases “Clouds beyond clouds” and “Wastes beyond wastes”, which define the vast scale of the natural world. The abstract noun “wastes” contributes to the bleak tone because its negative connotations enhance the apparent isolation and loneliness of the narrator. She has no control over her surroundings and is motionless while the present tense verb “blow” and the present progressive verb phrases “are darkening” and “is … descending” create a sense of on-going movement around her.

The narrator seems trapped – not just by the approach of night and the storm, but by something more intangible. This is clear in the abstract noun “spell”, with its connotations of bewitchment, and in the attributive modifier “tyrant” with its connotations of control and manipulation. It is also evident, however, in the very form of the poem itself. The tight rhyme structure mirrors the narrator’s feelings of being imprisoned: long vowel sounds (“blow/snow”) and even the words themselves (“me/go”) recur in an inescapable cycle. The grammatical structure of the sentences is cumulative: the comma splicing (ll.1-2) and the patterned sequence of initial position co-ordinating conjunctions (“But … And … And yet … But …”) drive the reader inescapably onwards. The mood of oppression is underpinned by dynamic verbs like “bound” and “weighed” as the poem builds to a climax in the repetition of the negative modal verb “cannot” (ll.4, 8). The initial position conjunction (“And”) and the caesura (l.4) make this an emphatic statement: the narrator feels physically and emotionally helpless.

The narrator seems trapped – not just by the approach of night and the storm, but by something more intangible. This is clear in the abstract noun “spell”, with its connotations of bewitchment, and in the attributive modifier “tyrant” with its connotations of control and manipulation. It is also evident, however, in the very form of the poem itself. The tight rhyme structure mirrors the narrator’s feelings of being imprisoned: long vowel sounds (“blow/snow”) and even the words themselves (“me/go”) recur in an inescapable cycle. The grammatical structure of the sentences is cumulative: the comma splicing (ll.1-2) and the patterned sequence of initial position co-ordinating conjunctions (“But … And … And yet … But …”) drive the reader inescapably onwards. The mood of oppression is underpinned by dynamic verbs like “bound” and “weighed” as the poem builds to a climax in the repetition of the negative modal verb “cannot” (ll.4, 8). The initial position conjunction (“And”) and the caesura (l.4) make this an emphatic statement: the narrator feels physically and emotionally helpless.

4. Change of direction

Where does the poem change? What has changed? What effect does it have?

The poet has built up a negative tone through her choice of words and the structure. The last line, however, moves us in a new direction. Instead of repeating the modal verb “cannot”, Brontë replaces it with “will not”. The change in meaning is significant – suddenly there is a sense of personal choice. The tone is emphatic: the positioning of the personal pronoun at the beginning of the line and the sequence of three consecutive stresses on the monosyllabic words reinforce this unexpected certainty. The change in tone is not sustained since “will” is quickly replaced by “cannot”, but for a moment there is an ambiguity that adds another dimension to the poem. The narrator both desires and fears the literal and figurative storm that envelops her.

It is at this point that we have to consider the title of the poem. The adjective phrase “Spellbound” repeats the  meaning of the simple sentence “(But) a tyrant spell has bound me” in an intensified form. As a grammatical fragment, it is a dramatic introduction, drawing our attention to an idea that is clearly going to be central to the poem’s meaning. The poet’s implicit repetition is a signpost that we need to pay particular attention to this. On first reading, we inevitably interpret the simple sentence as evidence that the narrator has been bewitched against her will because of the connotations of the words and the repetition of the negative modal verb in the next line. In the light of the final line and the title’s repetition of the idea, however, we need to reassess. There is an important ambiguity: as well as bewitched (negative), we feel that the narrator is also mesmerised, enthralled (positive). “Spellbound”: one word – two fields of reference. Some part of her finds a sensual pleasure in the physical and emotional storm. It is as though the passion of feeling, however painful, is better than the cold detachment of being numb.

meaning of the simple sentence “(But) a tyrant spell has bound me” in an intensified form. As a grammatical fragment, it is a dramatic introduction, drawing our attention to an idea that is clearly going to be central to the poem’s meaning. The poet’s implicit repetition is a signpost that we need to pay particular attention to this. On first reading, we inevitably interpret the simple sentence as evidence that the narrator has been bewitched against her will because of the connotations of the words and the repetition of the negative modal verb in the next line. In the light of the final line and the title’s repetition of the idea, however, we need to reassess. There is an important ambiguity: as well as bewitched (negative), we feel that the narrator is also mesmerised, enthralled (positive). “Spellbound”: one word – two fields of reference. Some part of her finds a sensual pleasure in the physical and emotional storm. It is as though the passion of feeling, however painful, is better than the cold detachment of being numb.

5. Conclusion

How does the context of the poem relate to its meaning?

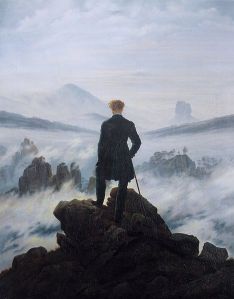

As a Romantic poet, Brontë draws on the natural world as a means of exploring her inner state of mind. She shows awe in the face of the storm’s natural magnificence and the tone is heightened by the intensity of her private experience. In a traditional lyric poem, we may expect the weak-strong iambic metre to be dominant. In Brontë’s poem, however, there are only three entirely iambic lines (ll.1, 5, 7). Since iambic metre is closest to the rhythms of informal speech and is often described as harmonious and lilting, Brontë chooses something more in keeping with the mood of her poem. Her experience is extraordinary and the disrupted metrical patterns reflect this. In some lines, the iambic rhythm is broken by a medial (ll.2,6) or initial spondee (ll.8, 11); in others, the dominance of trochees inverts the song-like melodies of iambs to create a harsher tone (ll.3-4, 9-10). The unpredictable metrical patterns result in an ecstatic expression of a profound experience as the poet tries to record something that is almost beyond words.

Brontë’s presentation of the natural world reflects the nineteenth century interest in the ‘sublime’ – an idea associated with an almost religious awe for the vastness and magnificence of the natural world, and with the expression of strong emotion. The Greek teacher Longinus (born around 213 AD, although very little is known about him) first explored the concept, describing the immensity of natural objects like stars, mountains, volcanoes and the oceans in his treatise ‘On the Sublime’. His work, translated into French in the seventeenth century, influenced the Romantics of the nineteenth century when Edmund Burke wrote a treatise entitled A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. This put a new emphasis on the element of violence in the natural world and Burke describes the power of experiences which are:

capable of producing delight; not pleasure, but a sort of delightful horror, a sort of tranquillity tinged with terror … Its object is the sublime. Its highest degree I call astonishment; the subordinate degrees are awe, reverence, and respect …

Brontë’s poem creates a sense of the natural world’s majestic grandeur and its violence. She is subsumed in the moment, immersed in a physical and emotional storm which does both horrify and delight. As readers, we are drawn into the world Brontë creates, experiencing the physical and emotional storm through the stark simplicity of her lyric.

Writing for exams

For those of you who are sitting examinations, this account of the poem fulfils the requirements of the main Assessment Objectives.

AO1

It is organised into paragraphs which logically develop, and it is written accurately. It uses a range of terminology at word class (abstract/concrete noun, adjective, dynamic/modal verb, adverb etc), phrase (noun phrase, present progressive verb phrase, adjective phrase) and sentence level (comma splicing, simple sentence, grammatical fragment). It also applies relevant concepts from literary frameworks (pathetic fallacy, tone, theme, narrator).

AO2

It addresses meaning in terms of the connotations of words and the groups of words which develop central themes. It explores the semantic effects of structural features (rhyme, caesura, metre) and form (lyric).

AO3

It considers the poem in its context in terms of changes to traditional genre (lyric), contemporary literary movements (the Romantic poets) and ideas (the sublime). It addresses reader-response.

And finally …

One important thing to remember is that the title of a poem cannot always be taken at face value – and it’s not always a good starting point for understanding the semantic richness of a poem. A title can be a defining limit, but it can also be a target. Having analysed a poem, therefore, it is important to revisit the title to see whether it can be reinterpreted. Think about its relationship with the poem as a whole, and look out for any semantic ambiguity.