Linguists can trace changes in the English language by studying texts and noting distinctive features of the words and the grammar at specific points in time. Focusing on language in this way as a sequence of snapshots in time is called a synchronic study of English.

The Bible offers us the perfect opportunity to look at how language changes because it has existed in so many versions and continues to be up-dated. Each time the language, grammar and style is changed, it tells us something about the English language and its users.

Using a sequence of extracts from Genesis 8 (the story of Noah and the flood), it is possible to see what kind of changes take place in language. The extracts come from versions written over a period of fifteen centuries, but this first post will begin with the Latin Bible to demonstrate the links between Latin and the English language.

St Jerome’s Vulgate Bible (382-405 AD)

St Jerome was mainly responsible for this translation of the Bible from the original Hebrew into Latin. This was the definitive edition  used in Britain throughout the Middle Ages and into the Early Modern period. Its name comes from the Latin vulgatus meaning ‘common’ or ‘popular’ – it was a translation written using the everyday style of fourth century Latin.

used in Britain throughout the Middle Ages and into the Early Modern period. Its name comes from the Latin vulgatus meaning ‘common’ or ‘popular’ – it was a translation written using the everyday style of fourth century Latin.

Although you may not be able to understand Latin, look at the extract below and see if you can find out anything about the language that is being used to tell the story of Noah.

This extract describes how Noah sends out first a raven and then a dove from his ark so that he can find out whether the land has begun to emerge from the flood waters. After the dove has returned, God speaks to Noah and tells him to leave the ark. Noah, his family and all the animals return to the land and Noah builds an altar to thank God.

(6) cumque transissent quadraginta dies aperiens Noe fenestram arcae quam fecerat dimisit corvum

(7) qui egrediebatur et revertebatur donec siccarentur aquae super terram

(8) emisit quoque columbam post eum ut videret si iam cessassent aquae super faciem terrae

(9) quae cum non invenisset ubi requiesceret pes eius reversa est ad eum in arcam aquae enim erant super universam terram extenditque manum et adprehensam intulit in arcam

(10) expectatis autem ultra septem diebus aliis rursum dimisit columbam ex arca

(11) at illa venit ad eum ad vesperam portans ramum olivae virentibus foliis in ore suo intellexit ergo Noe quod cessassent aquae super terram

(omitted text)

(15) locutus est autem Deus ad Noe dicens

(16) egredere de arca tu et uxor tua filii tui et uxores filiorum tuorum tecum

(omitted text)

(20) aedificavit autem Noe altare Domino et tollens de cunctis pecoribus et volucribus mundis obtulit holocausta super altare

Genesis 8 verses 6-11, 15-16, 20

The language here will look very strange unless you have studied Latin, but there are distinctive features to comment on even if we can’t read the language itself.

Lexis

- the preposition in is the same as in contemporary English (although our usage has come from Old English)

- some words look familiar

- quadraginta (L. forty) – contemporary English quadbike (N), quadruple (Adj, V) [meaning linked to ‘four’]

- aquae (L. waters) – contemporary English aqua (N), a light greenish-blue; aquatic (Adj), of the water; aquashow (N) [meaning linked to ‘water’]

- super (L. over/above) – contemporary English prefix: supermarket (N), supersonic (Adj), superimpose (V) [meaning linked to ‘above’, ‘beyond’, ‘in excess’]

- universam (L. whole, entire, all) – contemporary English universal credit, universal film rating

- terram (L. earth, land) – contemporary English terracotta (N, Adj), terrestrial (Adj) [meaning linked to’ earth’]

- ultra (L. beyond, more than) – contemporary English prefix: ultrasound (N), ultraviolet (Adj) [meaning linked to

‘beyond’]

‘beyond’]

- olivae (L. olive, olive tree) – contemporary English olive (N)

- altare (L. altar) – contemporary English altar (N)

- there are some words which are still used in English in subject specific contexts

- corvum (L. raven) – contemporary English Corvus (a scientific classification of birds in the crow genus)

- columbam (L. dove) – contemporary English Columba (a scientific classification of birds in the pigeon genus); columbary (dovecot)

- vesperam (L. evening, even-tide) – contemporary English vespers (in the Christian Church – evensong, evening service)

- ergo (L. therefore, well, then) – contemporary English therefore (used in formal contexts to mark the logical conclusion of an argument)

- the word holocausta (L. burnt offering, sacrifice wholly consumed by fire) now has more negative connotations

- from the late seventeenth century: complete destruction, especially of a large number of people; a great slaughter or massacre

- from 1942, capitalised: the mass murder of Jews in the Second World War

- from 1954, in the expression nuclear holocaust (to describe the potential scale of the destruction which a nuclear war would cause)

- if you have any knowledge of French (one of the Romance languages derived from vulgar Latin), you may have seen other words that are familiar

- fenestram (L. opening for light) – French fenêtre (window)

- est (L. 3rd person singular present tense verb ‘to be’) – French est (is) from être

- non (L. no, not, by no means) – French non (no)

- et (L. and, and even, also) – French et (and)

- venit (L. 3rd person singular past tense verb ‘to come’) – French venir (to come)

- qui (L. who) – French qui (who)

- si (L. if, whether) – French si (if)

- septem (L. seven) – French sept (seven)

- tu (L. you, thee) – French tu (you, singular familiar form)

- filii (L. son) – French fils (son)

The effect of Latin words on contemporary English

The word stock of the English language is a rich melting pot which is a result of all kinds of different linguistic influences (e.g. invasion, trade, cultural exchange, exploration) – and Latin is a significant part of this process. In this early period before the Germanic invasions, Latin was a spoken language which co-existed alongside the Celtic languages.

There was no direct contact between the first form of the English language (Old English) and Latin. The first Latin loan words in English therefore come either from borrowing Latin words adopted in the Celtic languages, or from borrowing Latin words in the Germanic languages.

Latin words in Germanic languages

The first Latin words entering the English lexicon are Anglo-Saxon words which had been adopted from Latin as a result of interaction with the Roman Empire. These borrowed words tend to be in lexical fields of trade, agriculture, administration and the military. Around 170 words were adopted before the 5th century invasions of the British Isles. For example, we can see words linked to food

- butter (Latin buturum; Old English butere)

- cheese (Latin caseus; Old English ciese)

to household goods

- dish (Latin discus; Old English disc)

- fork (Latin furca; Old English forca)

- table (Latin tabula; Old English tabul)

and building materials

- tile (Latin tegula; Old English tigule)

- pitch (Latin pix; Old English pic)

Other borrowed Latin words include:

- inch (Latin uncia; Old English ynce)

- pound i.e. weight (Latin pondo; Old English pund)

- mule (Latin mulus; Old English mul)

- cat (Latin cattus; Old English catte)

- toll (Latin teolonium; Old English toll)

Latin words in Celtic languages

The Celts lived under Roman occupation for more than three centuries, but Latin did not replace their native languages as had happened in Gaul under the Roman occupation. Before the Romans left in 410AD, a number of borrowed Latin words had been adopted by the Celts. After the invasions of the 5th and 6th centuries, as the Germanic tribes began to settle in England, some of these words of Latin origin were adopted by the Anglo-Saxons. This linguistic exchange was limited, however, because the Celtic peoples were driven to the edges of the country, with their languages effectively isolated from Old English. Those who were Romanized and used Latin tended to be of a higher social class, or to live in cities.

In English, we find evidence of this early linguistic borrowing from Latin in place names like Chester and Winchester which had originally been Roman encapments (Latin castra, camp; Old English ceaster) and in traded goods like wine (Latin vinum; Welsh gwin; Irish fín; Old English win).

In English, we find evidence of this early linguistic borrowing from Latin in place names like Chester and Winchester which had originally been Roman encapments (Latin castra, camp; Old English ceaster) and in traded goods like wine (Latin vinum; Welsh gwin; Irish fín; Old English win).

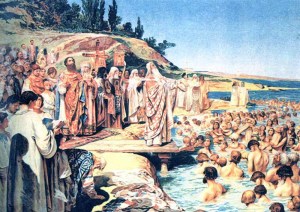

Latin words linked to the introduction of Christianity

The final early period of Latin borrowing is linked directly to the adoption of Christianity by the Anglo-Saxons at the end of the sixth  century. The impact of this cultural change was felt for several centuries afterwards with Latin loan words appearing in Old English into the 11th century. It becomes easier for us to identify borrowings in this period because of the survival of written texts. Many of the words borrowed are related to religion and religious practices.

century. The impact of this cultural change was felt for several centuries afterwards with Latin loan words appearing in Old English into the 11th century. It becomes easier for us to identify borrowings in this period because of the survival of written texts. Many of the words borrowed are related to religion and religious practices.

- candle (Latin candela; Old English candel)

- disciple (Latin discipulus; Old English discipul)

- martyr (Latin martyr; Old English martyr)

- organ (Latin organum; Old English organe)

The monasteries were important centres of scholarship and many words linked to learning were also adopted at this time.

- school (Latin schola; Old English scol)

- verse (Latin versus; Old English fers)

- epistle – now archaic, replaced by ‘letter’ (Latin epistula; Old English epistole)

Other words reflect changes in domestic life.

- pear (Latin pera; Old English peru)

- ginger (Latin gingiber; Old English gingiber)

- mussel (Latin muscula; Old English mucxle)

- plant (Old Latin planta; Old English planta)

The examples above are all nouns, but verbs were also borrowed

- to turn (Latin tornare; Old English tyrnan)

- to temper (Latin temperare; Old English temprian)

- to spend (Latin expendere; Old English spendan)

The Latin words adopted from this early period reflect changes in the lives of the Britons as their experiences were broadened by new customs and practices. The borrowed words were blended completely with the native vocabulary and it is only the polysyllabic structure that suggests their Latinate origin to a speaker of contemporary English.

Grammar

Latin grammar is very different to contemporary English because Latin is an inflected language and English is a word order language. This means that Latin depends on word endings (inflections) to tell us what job each word is doing in a sentence, while in contemporary English we can look at the position of a word in a sentence. Old English, on the other hand, like Latin, is an inflected language and when we look at the next example of the Noah story, you will see similarities in the way that grammatical relationships are sign-posted.

Prefixation

Latin uses a wide range of prefixes to change the meaning of verbs. In the Noah extract, we can see dimisit (from dimittere, to send away) and emisit (from emittere, to send out). Other variations include amisit (from amittere, to lose/send away), demisit (from demittere, to send down/lower), remisit (from remittere, to send back) and omisit (from omittere, to lay aside/omit). All these verbs are formed from the addition of prefixes to the verb mittere (to send).

We also form verbs like this in contemporary English using some of the same Latin prefixes:

debrief (reversal of process)

dislike (not)

replant (again)

transplant (across)

Case

You may have noticed that some words appear several times with different endings (e.g. terram, terrae). The seven grammatical cases in Latin dictate what endings nouns, pronouns, determiners and adjectives should have.

- nominative – subject of a sentence

- accusative – direct object of a sentence

- genitive – marks possession (in English ‘of’ or possessive apostrophe)

- dative – indirect object in a sentence (in English ‘to’ or ‘for’)

- ablative – follows some prepositions and verbs (in English ‘from’, ‘by’ or ‘with’)

- locative – marks location (in English ‘at’)

Nouns are classified as feminine, masculine or neuter and each case has distinctive endings to show this.

The nominative case (subject) of ark is ‘arca (feminine noun). In the Noah extract, we see it in the following forms:

- fenestram arcae – genitive inflection [i.e. the window of the ark]

- in arcam – accusative inflection: the preposition in is always followed by the accusative case where the meaning is ‘into’ [i.e. into the ark]

- ex arca – ablative inflection: the preposition ex is always followed by the ablative case [i.e. out of the ark]

- de arca – ablative inflection: the preposition de is always followed by the ablative case [i.e. down from the ark]

The accusative case (object) inflections can be seen to change according to the classification of the nouns:

- corvum – accusative masculine inflection (nominative form corvus)

- columbam – accusative feminine ending (nominative form columba)

Because words that are linked in meaning do not always appear next to each other, inflections help us to recognise linguistic units – for example, adjective + noun, possessive determiner + noun.

- super universam terram – the preposition super takes the accusative case so the adjective universus and the feminine noun terra need a feminine singular accusative inflection [i.e. over the whole earth]

- virentibus foliis – the translation is ‘with’ so the neuter noun folium (leaf) and the present participle of the verb vivere (to be green) functioning as an adjective need ablative neuter plural inflections [i.e. with green leaves]

- cunctis pecoribus et volucribus mundis – the co-0ordinated nouns (the cattle and the birds), the pre-determiner (cunctis, all) and the adjective (mundis, clean) must all have ablative plural inflections

Determiners and pronouns

If you look at the nouns in the Noah extract, you will see that there are no definite articles preceding them. In Latin, they are understood as part of the noun – in translating into English we would add a definite article (the) or an indefinite article (a/an) according to the context. This is an example of English as a periphrastic language – it needs to use several words where Latin can use one.

- altare = the altar, an altar [in the Noah extract, an indefinite article is more appropriate]

Similarly, verbs can be used without a pronoun.

Possessive determiners are used to make relationships clear.

You can see evidence in this example of the difference between English as a word order language and Latin as an inflected language. The noun (sons) precedes the possessive determiner (your), but their linguistic relationship is clear because both have a nominative plural masculine inflection.

Possessive nouns

Because Latin uses genitive case inflections on nouns and any related words to mark the possessive, the use of prepositional of phrases or the possessive apostrophe has not yet emerged. The periphrastic genitive (e.g. ‘of the ark’) is another example of English needing to use a group of words where Latin can use one.

- faciem terrae – the accusative singular of the feminine noun facies (face, surface) is followed by the genitive singular feminine form of terra (earth) [i.e. the surface of the earth; the earth’s surface]

- ramum olivae – the accusative singular of the neuter noun ramus (branch) is followed by the genitive singular neuter form of oliva (olive, olive tree) [i.e. the branch of an olive, an olive’s branch]

- uxores filiorum tuorum – the nominative plural of the feminine noun uxor (wife) is followed by the genitive plural masculine form of filius (son) and tuus (your) [i.e. the wives of your sons, your sons’ wives]

Verbs

Endings are also important on Latin verbs. In contemporary English, we still use a limited number of verb inflections e.g. (simple present tense third person singular -s inflection; simple past tense -ed inflection; -ing participle inflection), but we also use groups of verbs (periphrastic verbal forms) to indicate different time scales (aspect), shades of meaning (modal verbs) and voice (active/passive). Where Latin can use a single verb with a distinctive inflection, you will find that the English translation requires several words (e.g. pronouns and primary/modal auxiliary verbs may precede a lexical verb, which may be followed by prepositions and adverbs). We therefore describe Latin as an inflected language and English as periphrastic.

By looking at some of the verbs in the Noah extract, we can see how the endings are used as signposts.

1. Active verbs

Active verbs are the most common verb forms – the grammatical subject is responsible for the action or process of the verb and is marked in Latin by a nominative inflection.

Perfect

Perfect stem + 3rd person singular -it inflection (translates in English as -ed, have -ed)

- dimisit = strong perfect stem dimis- (from dimittere, to send away)

- emisit = strong perfect stem emis- (from emittere, to send out)

- extendit = regular stem extend- (from extendere, to stretch out)

aperiens Noe fenestram arcae quam fecerat dimisit corvum

opening the window of the ark that he had made, Noah sent away a raven

(dimisit = verb + adverb)

Imperfect

Infinitive or reduced infinitive + 3rd person singular -ebatur inflection (translates literally as ‘was/were -ing‘, though in Latin-English translations it is often better translated as the simple past)

- egrediebatur = 3rd person singular (from egredi, to go/come out)

- revertebatur = 3rd person singular (from revertere, to turn back/go back)

- erant = 3rd person plural, irregular (from esse, to be)

corvum qui egrediebatur

a raven which went out

(egrediebatur = lexical verb + adverb)

2. Subjunctive verbs

The subjunctive is very common in Latin: it follows certain conjunctions (cum, ut, donec) and is used in specific constructions such as purpose and result clauses. In contemporary English, the subjunctive has almost disappeared, although we still use it in some set phrases (God Save the Queen), very formal commands (I insist that he be punished now), and in hypothetical conditional clauses (If I were to …). It can be recognised by the non-agreement of the subject and verb (God saves; he is punished; If I was …)

Imperfect

Infinitive + 3rd person singular -t inflection (translates as ‘might + infinitive’ or ‘to + infinitive’)

- (ut) videret = 3rd person singular (from videre, to see)

- (cum) requiesceret = 3rd person singular (from requiescere, to rest)

quae cum non invenisset ubi requiesceret pes eius reversa est ad eum

when she had not found where she might rest her foot, she returned to him

(requiesceret = pronoun + modal auxiliary + lexical verb)

Pluperfect

Perfect stem + 3rd person plural -(i)ssent inflection (translates as ‘had + -ed or ‘would + infinitive’)

- (cum) transissent = 3rd person plural (from transire, to pass by)

- (si) cessassent = 3rd person plural (from cessare, to cease from/be free of)

- (cum) invenisset = 3rd person singular plural (from invenire, to find)

emisit quoque columbam post eum ut videret si iam cessassent aquae super faciem terrae

he also sent a dove after him (the raven) to see whether the waters above the surface of the earth had ceased

(cessassent = primary auxiliary + lexical verb)

3. Passive verbs

Passive verbs in Latin are indicated by a distinctive set of endings which signpost that the object of a sentence appears in the nominative case – the grammatical subject of the sentence may be omitted or will appear in the ablative case after a/ab (by + agent).

Imperfect subjunctive

Infinitive + 3rd person plural -entur inflection (translates as ‘were + -ed‘)

- (donec) siccarentur = 3rd person plural (from siccare, to dry up)

et revertebatur donec siccarentur aquae super terram

and did (not) return until the waters over the earth were dried up

(siccarentur = primary auxiliary + lexical verb + adverb)

4. Participles

Present

Remove -re from the infinitive and add –ens/-ans inflection to the stem (translates as -ing)

- aperiens = from aperire, to uncover/open

- portans = from portare, to carry

- tollens = from tolle, to lift/raise

at illa venit ad eum ad vesperam portans ramum olivae virentibus foliis in ore suo

but she came to him towards evening carrying the branch of an olive with green leaves in her mouth

Perfect passive

Remove -re from the infinitive and add -tus inflection – this ending is then inflected like an adjective according to case and number (translated as a clause e.g. ‘having -ed‘ or ‘When he had -ed …’)

- adprehensam = from adprehendre, to seize/grasp

- expectatis = from expectare, to await, wait for

expectatis autem ultra septem diebus aliis rursum dimisit columbam ex arca

but having waited for more than seven other days, he sent away the dove from the ark again

(expectatis = primary auxiliary + lexical verb + preposition)

The effect of Latin grammar on contemporary English

Latin is an inflected language and English is a word order language. This means that the grammar systems of each language are now very different – a change which has come about over a long period of time. Old English (from around 450-1150) is often known as the period of full inflections because at this point nouns, determiners, pronouns, adjectives and verbs were inflected. During the Middle English period (1150-1500), the number of inflections were significantly reduced and it is often known as the period of levelled inflections. By the Modern English period (1500-1900), almost all inflections were redundant – it is therefore called the period of lost inflections. In contemporary English, we use very few inflections:

-s/-es/-ies → plural (noun)

‘s/s’ → possession (noun)

–ly → to form an adverb from an adjective

-s → 3rd person singular present tense (verb)

-ed → simple past tense and past participle (regular verb)

-ing → present participle (verb)

We can also see the remains of a case system in the form of some of our pronouns:

Subject (nominative) I he they who

Object (accusative) me him them whom

Beyond this, the principles of Latin grammar can be seen in some of the traditional prescriptive rules which are still sometimes cited as principles of ‘correct’ English usage.

Split infinitives

In Latin, it is not possible to split an infinitive since the preposition to is bound up in the meaning of the verb itself. Traditionalists have, therefore, always considered separating the preposition from its verb to be ‘wrong’ in English – despite the fact that there are examples of its usage in writers from the Middle Ages onwards.

While it is still often frowned upon in formal writing, there are clearly cases where splitting the infinitive has no effect (informal conversation!) and where it can be used for dramatic effect …

To magically exist beyond the parameters of our known world, to self-consciously seek beyond the limitations of the human brain, that is my quest.

for emphatic effect …

To really understand you have to do the experiments yourself.

or for humorous effect…

‘To boldly stagger, walk, jog, run or sprint’ is a great motto for all parkrun’s Saturday morning get-fitters!

Stranded prepositions

Since the seventeenth century and the poet John Dryden’s attack on dangling prepositions, traditionalists have disliked sentences that end with a preposition. The word itself comes from Latin: prae- (before) + posito (having been placed) and Latin usage dictates that  the preposition should always precede the noun/pronoun to which it relates (or … which it relates to!). In English, however there is no such rule.

the preposition should always precede the noun/pronoun to which it relates (or … which it relates to!). In English, however there is no such rule.

In contemporary English usage, it is perhaps safer in formal writing to reorder the words to avoid dangling prepositions, but it is equally important to avoid awkward or clumsy constructions – sometimes a sentence-final preposition is easier to hear and understand (particularly with multi-word verbs ). Since language is all about communicating meaning, ultimately clarity is most important.

To whom should I address my application?

(appropriate in a formal written context)

Who can I sit next to?

(appropriate in informal conversation)

Everything was sent back because the clothes hadn’t been paid for.

Everything was sent back because paid for the clothes hadn’t been.

(moving the preposition results in an awkward sentence which is far more difficult to understand)

And finally …

For those of you who have made it this far and want to have a go at reading the Latin extract in full, here are notes on the words which haven’t been addressed elsewhere in this post:

- cumque: and with (enclitic que i.e. joined at the end of the preceding word to form a single unit)

- dies: days (nominative plural of dies, masculine noun)

- enim: for

- que: and

- manum: hand (accusative singular of manus, feminine noun)

- intulit: brought in (irregular 3rd person singular perfect of inferre)

- intellexit: understood (3rd person singular perfect of intellegere)

- quod: that

- locutus est: spoke (3rd person singular perfect of loqui)

- autem: but

- Deus: God (nominative singular, masculine noun)

- ad: to, towards (+ accusative)

- dicens: saying (present participle of dicere)

- egredere: Go out (imperative of egredi)

- uxor: wife (nominative singular, feminine noun)

- tua: your (nominative singular, feminine possessive determiner)

- tecum: with you (ablative singular, second person pronoun te with enclitic cum)

- Domino: to the Lord (dative singular of dominus, masculine noun)

- de: from (+ ablative)

- obtulit: offered (irregular 3rd person singular perfect of offerre)

The ‘h’ in yoghurt is also in the process of disappearing. Typing yoghurt into a search engine gives 28,700,000 hits, but typing yogurt produces 154,000,000 hits. This reflects the kind of findings Crystal has reported for ‘rhubarb’.

The ‘h’ in yoghurt is also in the process of disappearing. Typing yoghurt into a search engine gives 28,700,000 hits, but typing yogurt produces 154,000,000 hits. This reflects the kind of findings Crystal has reported for ‘rhubarb’.